By PTLB

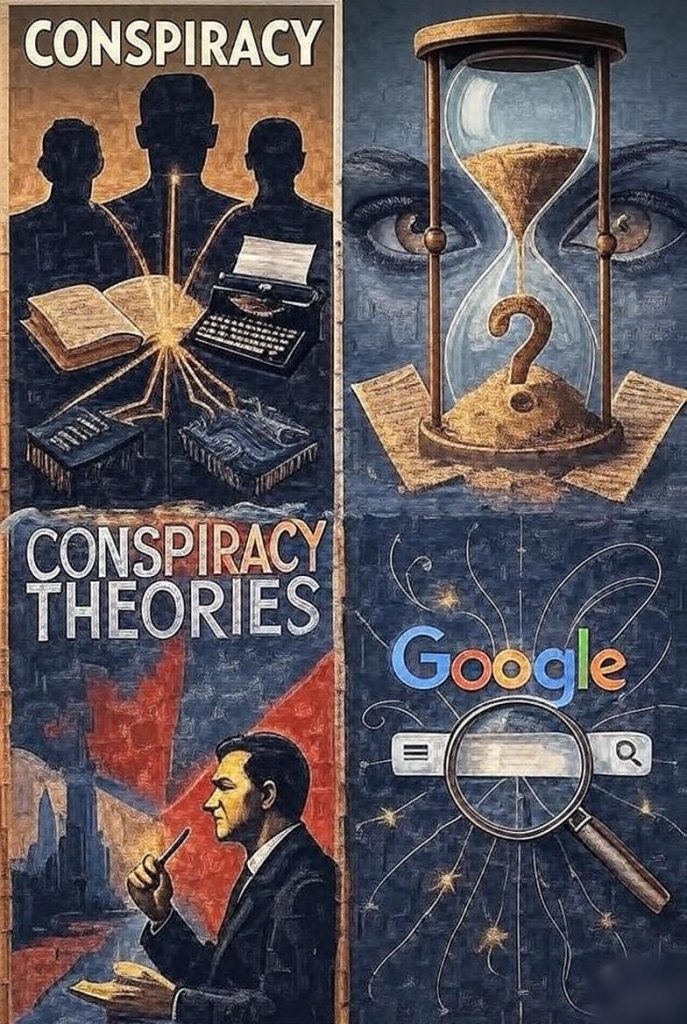

October 11, 2025 – The term “conspiracy theory” first appeared in American newspapers and legal contexts in the mid-19th century. It described explanations of secret plots or coordinated actions by individuals or groups. One early use came in 1863. Reports on President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination called speculative accounts of the event conspiracy theories. The phrase grew common in the 1870s and 1880s. Media used it after the 1881 shooting of President James A. Garfield to label unverified claims about accomplices or larger plots. By the early 20th century, the term entered academic discussions. Philosopher Karl Popper helped popularize it in the 1950s. In his book The Open Society and Its Enemies, he used it to criticize simple explanations of history as intentional group actions instead of complex social forces. Some people claim the Central Intelligence Agency invented the phrase in 1967 to discredit critics. This idea is a meta-conspiracy theory. In fact, the term existed over a century earlier. However, its negative meaning grew stronger after World War II.

In the mid-20th century, the term gained attention during talks about the 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Declassified U.S. intelligence documents show officials and media used the label to push aside alternative views. They called these views unfounded speculation. This fit larger efforts to shape public opinion in the Cold War. Today, in the digital world, search engines and social platforms use algorithms to control content visibility. These tools often favor established sources over new or opposing ones linked to conspiracy theories. This raises questions about information control. Technology now acts like past media influences. It affects access to different viewpoints in an algorithm-driven world.

The Central Intelligence Agency started building ties with media outlets and journalists in the late 1940s. This was part of its Cold War role to fight Soviet influence and shape global stories. People call this Operation Mockingbird (not Project Mockingbird). The CIA never confirmed the name. It involved recruiting or working with hundreds of American reporters. They gathered intelligence, placed stories, and spread agency-approved information at home and abroad. The program began in 1948. The CIA’s Office of Policy Coordination used journalistic networks for propaganda. It grew more organized in the 1950s under Director Allen Dulles. Declassified files from congressional reviews show these links reached major services like the Associated Press and United Press International. They also included broadcasters such as CBS and NBC. Journalists gave cover for secret operations. In return, they got exclusive access or shared anti-communist views.

These ties faced strong review in the 1975 Church Committee hearings. Senator Frank Church led the Senate group that looked into intelligence abuses after news of domestic spying and killings. The final report, Intelligence Activities and the Rights of Americans, explained how the CIA had over 400 U.S.-based media contacts by the mid-1970s. This included full-time reporters and freelancers who sent information to the agency. They also put agency views into their stories. CIA Director George H.W. Bush issued a 1976 order to stop paying journalists directly. Still, the committee found informal work continued. This showed problems in keeping journalism separate from intelligence. The findings led to changes like more congressional watch and limits on domestic propaganda. Critics say the full impact of Mockingbird on public talk stays hidden because of destroyed records.

A 1977 article by journalist Carl Bernstein in Rolling Stone gave a full look at CIA-media links. Bernstein spent six months interviewing ex-agency officials and reviewing declassified files. He said at least 400 American journalists worked for the CIA over 25 years. Their tasks went from basic intelligence to spreading propaganda. He named key people like CBS’s Arthur Hays Sulzberger and Time magazine’s C.D. Jackson. He described how papers like The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Reuters had CIA helpers. These people shaped stories on events like the Bay of Pigs invasion and Vietnam War buildup. Bernstein’s article, “The CIA and the Media,” showed the mutual benefits. Journalists got tips. The agency got cover. This led to less trust in mainstream news.

One clear example is CIA Dispatch 1035-960. This classified memo from April 1, 1967, was declassified in 1976 under the Freedom of Information Act. It went to over 3,000 CIA contacts in media around the world. Titled “Countering Criticism of the Warren Report,” the 13-page document gave advice on fighting doubts about the Warren Commission’s finding that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone in killing President Kennedy. It told assets to stress the commission’s strong evidence. It said to question critics’ motives, like links to communists or money gains. It pushed using “conspiracy theory” to call alternative ideas irrational or driven by politics. The dispatch suggested talking about “conspiratorial aspects” of the assassination only to show they were unlikely. The goal was to give material to counter and discredit claims without open censorship. This memo did not create the term. But it stepped up its use as a tool to shape stories. It affected coverage in places like Time and The Saturday Evening Post. It set a model for handling later issues.

As the internet made information open to all in the 21st century, search engines like Google became key controllers of online knowledge. Their algorithms decide what billions see for daily searches. After worries about misinformation grew—fueled by events like the 2016 U.S. election with fake stories on social media—Google started Project Owl in April 2017. Named for the wise bird in myths, the project aimed to boost good results and lower bad ones like fake news. It did this without changing single searches by hand. The plan had three parts. First, machine learning updates found and pushed down bad pages from top spots. Second, more human raters trained algorithms on what makes content expert and reliable. Third, new tools let users report results to improve the system. Google said these changes would favor “authoritative content” from trusted sites. It used signs like source skill and fact-check matches. At first, it touched about 4% of searches. Critics like digital rights groups worried it might bias results to mainstream views. This could hide real investigations or minority ideas while fighting lies.

The hidden nature of these algorithms got more attention in late May 2024. Internal files from Google’s Content Warehouse API leaked by mistake through a GitHub post in an open-source library. The leak had over 2,500 documents from 2019 to 2023. They detailed more than 14,000 factors that affect search rankings. Examples include “siteAuthority” for domain trust, “contentFreshness,” and user details like “YourMoney isGoogleVisitor” for financial advice based on if the searcher works at Google. The files showed things against Google’s public words, like click data in rankings despite denials. They also showed special handling for topics like elections or health lies to push diverse views while lowering poor sources. Other notes covered demotions for spammy loan sites and “YMYL” rules for key queries on money or life. This highlighted human input in automated choices. Google said the files were real but old, incomplete, and not current. It blamed an engineer’s slip in a third-party spot. SEO pros and researchers called the leak a rare look inside search’s “black box.” It led to calls for more openness and rules. But it did not show direct ways to block “conspiracy theory” content. This event links to old worries about handling information. It shows how tech platforms balance user safety and free speech today.

A pattern runs through 20th-century U.S. history. Officials deny hidden actions at first. Then, news reports, leaks, or reviews reveal them. These cases cover medical wrongs, spy work, and military tricks. Authorities and media often called them “conspiracy theories” until evidence came out. This led to blame and fixes. These examples show weak spots in checks. They also shape talks on openness today. They prove doubt can turn to real critique with proof. Many cases involve Cold War tests with biology and chemicals for defense. Here is a table of key examples.

| Event | Description | Confirmation and Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932–1972) | U.S. Public Health Service observed the progression of untreated syphilis in 399 Black men in Alabama, withholding penicillin after its availability in 1947. Participants were not informed of their diagnosis. | Exposed by an Associated Press report in 1972; led to a 1974 lawsuit settlement of $10 million and the 1979 Belmont Report on research ethics. At least 128 participants died from the disease. |

| MKUltra (1953–1973) | CIA program involving LSD and other substances administered to unwitting subjects, including U.S. and Canadian citizens, for mind-control research. Conducted at universities, hospitals, and prisons. | Declassified in 1975 Church Committee hearings; over 20,000 documents released. Resulted in a 1977 CIA apology and limited compensation via lawsuits; at least a dozen deaths linked to experiments. |

| Project Midnight Climax (1953–1965) | CIA subproject of MKUltra that operated safe houses disguised as brothels in San Francisco and New York City. Agents used prostitutes to lure clients, who were then dosed with LSD without consent and observed through two-way mirrors for behavioral effects. | Declassified in 1977 as part of MKUltra documents; confirmed during Senate hearings. Led to ethical reforms in human experimentation; no direct compensation, but highlighted in broader MKUltra apologies. |

| Operation Sea-Spray (1950) | U.S. Navy released Serratia marcescens and Bacillus globigii bacteria over San Francisco from ships to simulate a biological attack and assess urban vulnerability. This exposed approximately 800,000 residents, leading to urinary tract infections and at least one death. | Declassified in 1977 during Senate hearings on biological testing; confirmed by military records and a 1981 lawsuit (dismissed on sovereign immunity grounds but acknowledging the event). |

| Gulf of Tonkin Incident (1964) | U.S. reports of North Vietnamese attacks on American ships on August 2 and 4, 1964, prompted the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, escalating the Vietnam War. The second attack was later found to be exaggerated or nonexistent based on misinterpreted sonar data. | Declassified NSA documents in 2005 confirmed the discrepancies; no formal apology issued, but acknowledged as a “mistake” by officials. Contributed to over 58,000 U.S. military deaths. |

| COINTELPRO (1956–1971) | FBI operation that illegally spied on, infiltrated, and disrupted dissident political organizations, targeting civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., anti-Vietnam War protesters, and minority rights groups through smear campaigns and provocations. | Exposed in 1971 when activists stole files from an FBI office; confirmed by Senate hearings in 1975–1976, leading to the program’s termination and reforms in FBI oversight. |

| Operation Northwoods (1962) | Pentagon proposal by the Joint Chiefs of Staff to stage false-flag terrorist attacks on U.S. soil, including hijackings and bombings, and blame them on Cuba to justify military invasion. | Declassified in 1997 as part of the John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act; the plan was rejected by President Kennedy but revealed formal military endorsement of such tactics. |

| Operation Paperclip (1945–1959) | Secret U.S. program that recruited over 1,600 German scientists, engineers, and technicians, many with Nazi affiliations and war crime records, to work on American military and space projects while concealing their pasts. | Declassified in the 1970s and 1980s through Freedom of Information Act requests; confirmed by government records and historical analyses. Contributed to U.S. advancements in rocketry but raised ethical concerns about employing former Nazis. |

| Government Poisoning of Alcohol During Prohibition (1920–1933) | U.S. Treasury Department mandated the addition of toxic chemicals, including methanol, to industrial alcohol to deter its diversion into bootleg liquor, knowing it would be consumed by the public. | Confirmed by historical records and declassified policy documents; estimated to have caused up to 10,000 deaths. Ended with the repeal of Prohibition in 1933. |

| NSA PRISM Surveillance Program (2007–2013 revelation) | National Security Agency program collecting internet communications data directly from U.S. tech companies like Google and Facebook, including emails and chats of American citizens, without warrants. | Revealed by Edward Snowden’s 2013 leaks of classified documents; confirmed by subsequent congressional investigations and court rulings declaring parts unconstitutional. Led to reforms in surveillance laws. |

This table lists a few cases. Many more verified conspiracies exist in records. At the same time, many claims labeled as conspiracy theories have been claimed to be false. Each of these so called debunked theory needs its own check.

Conclusion

The path of the “conspiracy theory” label runs from 19th-century news roots to its use as a weapon in Cold War media to its control by algorithms today. This shows steady work to shape how people understand big events. The CIA’s Operation Mockingbird and Dispatch 1035-960, revealed by the Church Committee and Bernstein’s report, show how spy groups built close links with news to guide stories. This happened especially around the Kennedy killing. It made the term a harsh label that still fuels doubt in leaders. These 20th-century moves, pushed by world politics needs, boosted secret work and planted distrust. This matches the hard choices of today’s info keepers.

Now, Google’s Project Owl and the 2024 Content Warehouse leak show the complex tools of search control. Factors like site trust and newness aim to stop misinformation but can lock in bubbles by picking big sources. This new form of story control reacts to election shocks and fast lies. It looks like past examples but adds big, hidden automation that helps and hurts. The cases listed—from the Tuskegee Study’s trust break and MKUltra’s drug tests, including Project Midnight Climax’s hidden watches, to Operation Sea-Spray’s germ trials, the Gulf of Tonkin lie, COINTELPRO’s group attacks, Northwoods’ stopped fake attacks, Paperclip’s past compromises, Prohibition’s poison hides, and PRISM’s secret data grabs—prove that ignored ideas can become true facts with proof. This stresses the need for careful, proof-based questions.

These linked pasts highlight a lasting push and pull between safety needs, tech growth, and open democracy in info flows. They make us think about care: How do we balance stopping real harms like lie spreads with keeping open talks? Wins after the Church Committee, like bigger FOIA use, Belmont ethics rules, and Snowden-led spy changes, show how people and Congress can fix power gaps. As AI tools grow, groups of rule-makers, creators, thinkers, and active people must push for clear checks, fair designs, and strong lessons on judging sources to close these gaps.

In this fast-linked world, where info moves quick and sways group actions, one main idea holds: Doubt based on proof builds strong democracy, not weak ones. By learning these true histories, we can make knowledge systems that value finds and blame over blind rule.